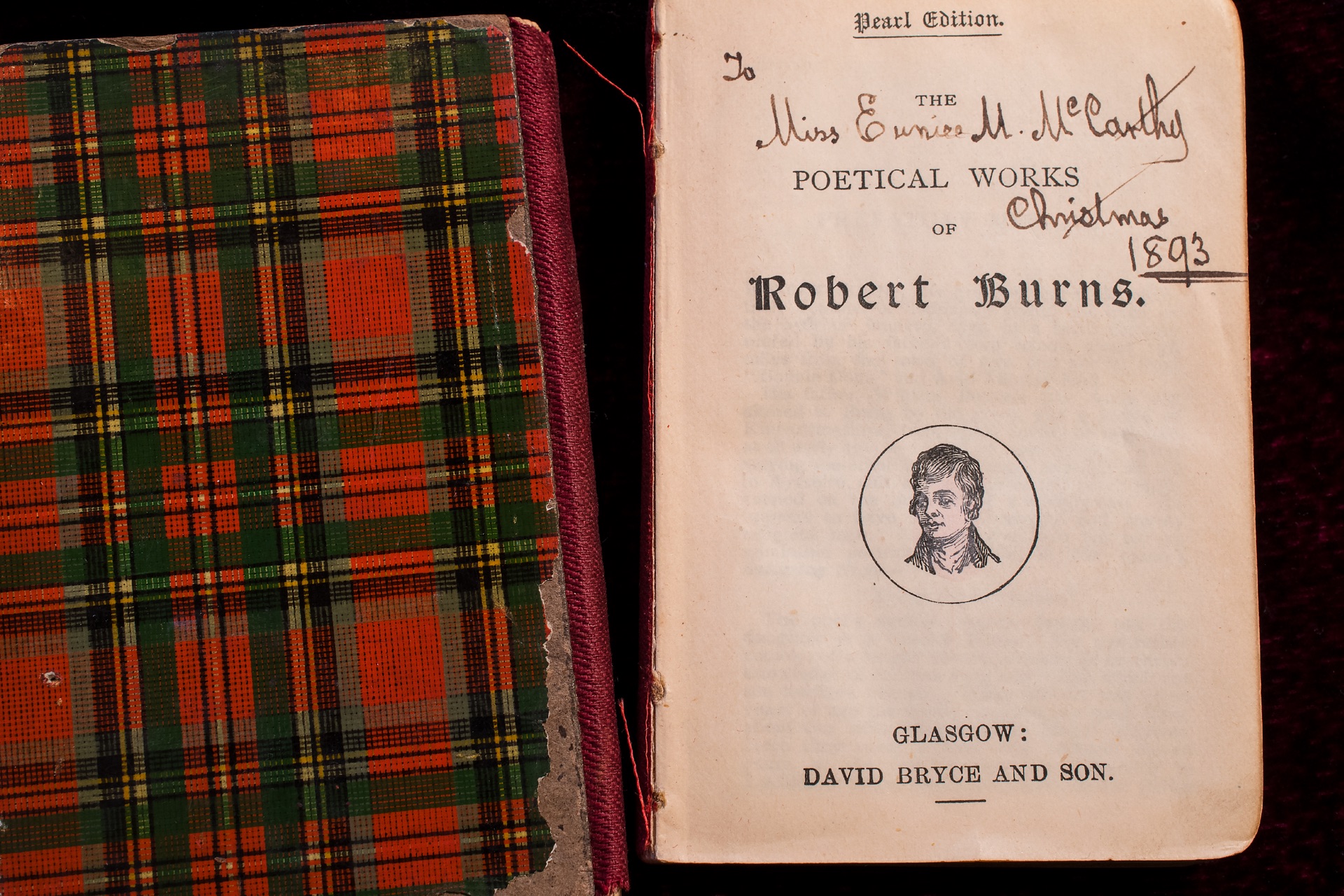

I have always loved the physicality of books. These belonged to my father’s aunt, Eunice and Eunice’s brother, Paul. They were both aspiring writers. They also kept books that belonged to their brother, my paternal grandfather, Justin.

On childhood visits to Eunice and Paul in their NYC apartment, I saw books everywhere. Later on, visiting Eunice in a nursing home, we always found her reading.

After her death, her belongings were stored in my parent’s garage; years later, when my parent’s house was sold, some of those boxes found their way to me.

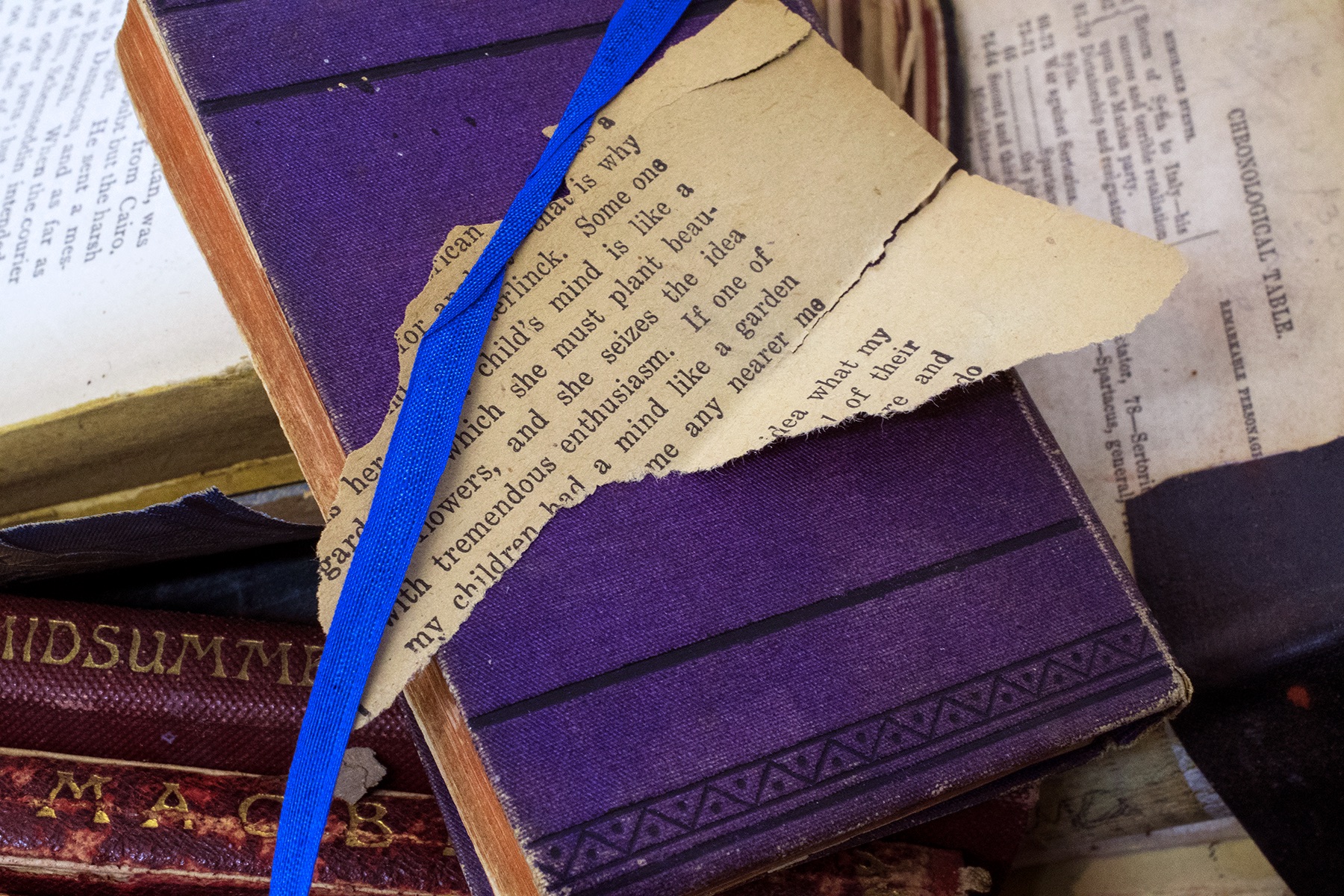

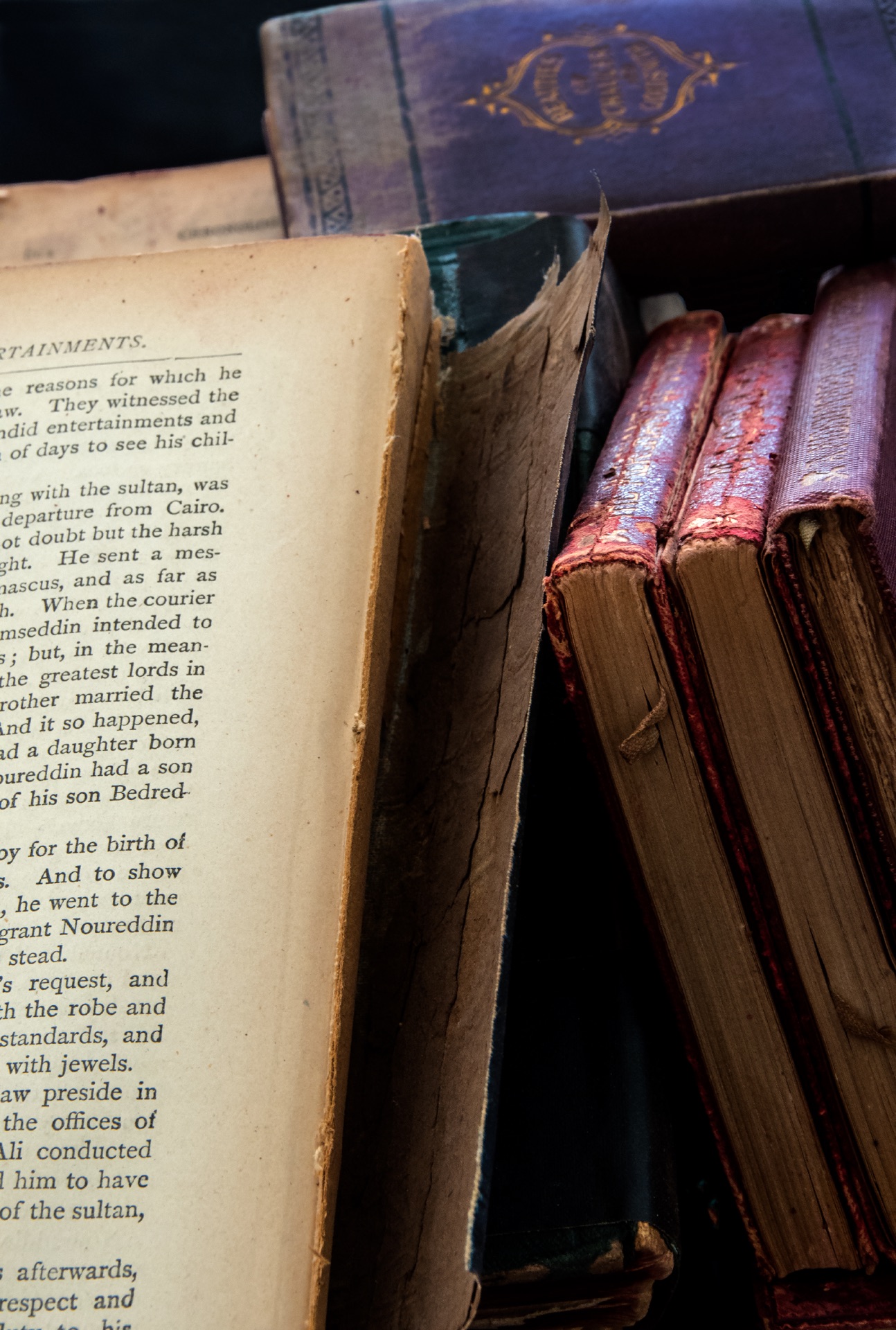

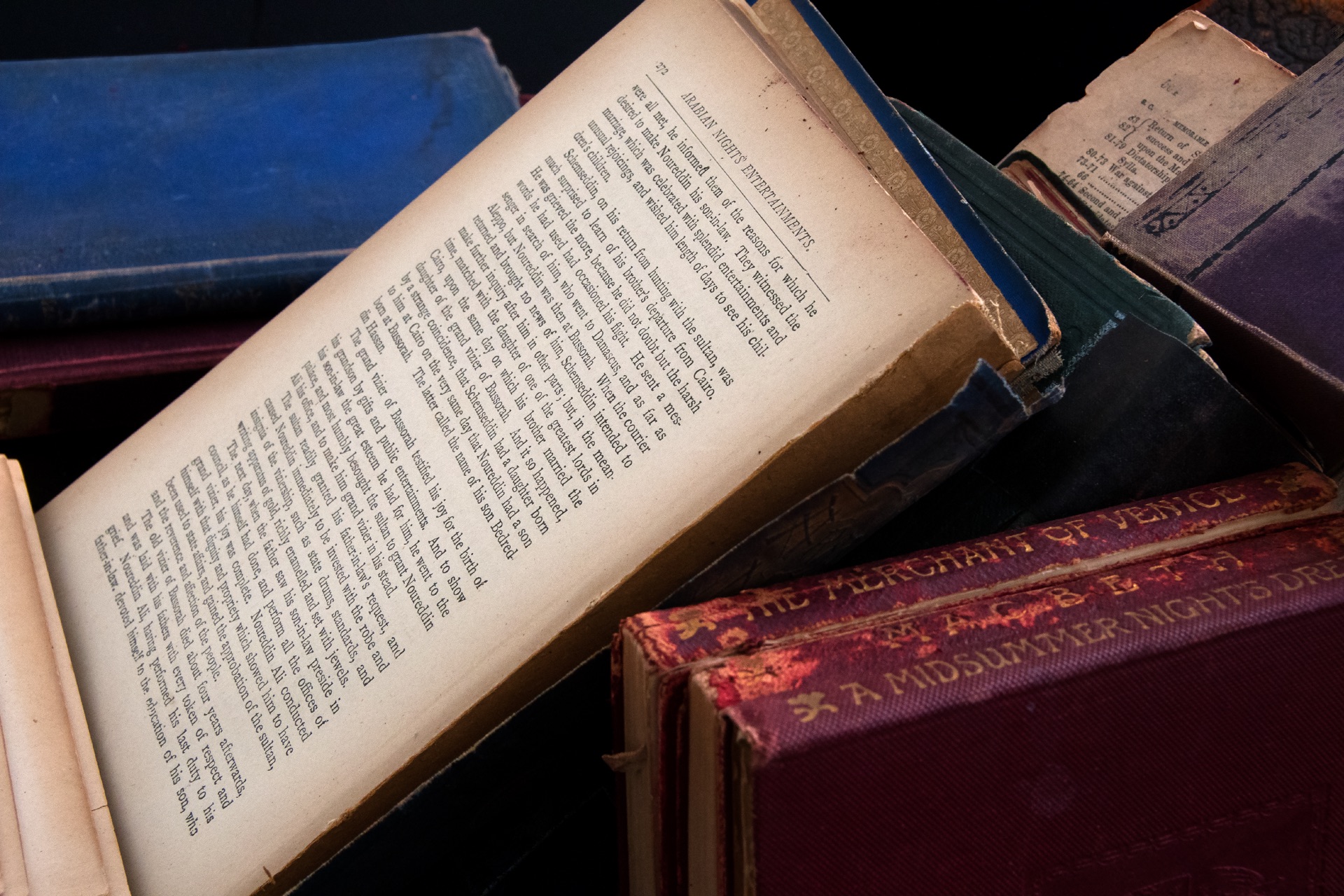

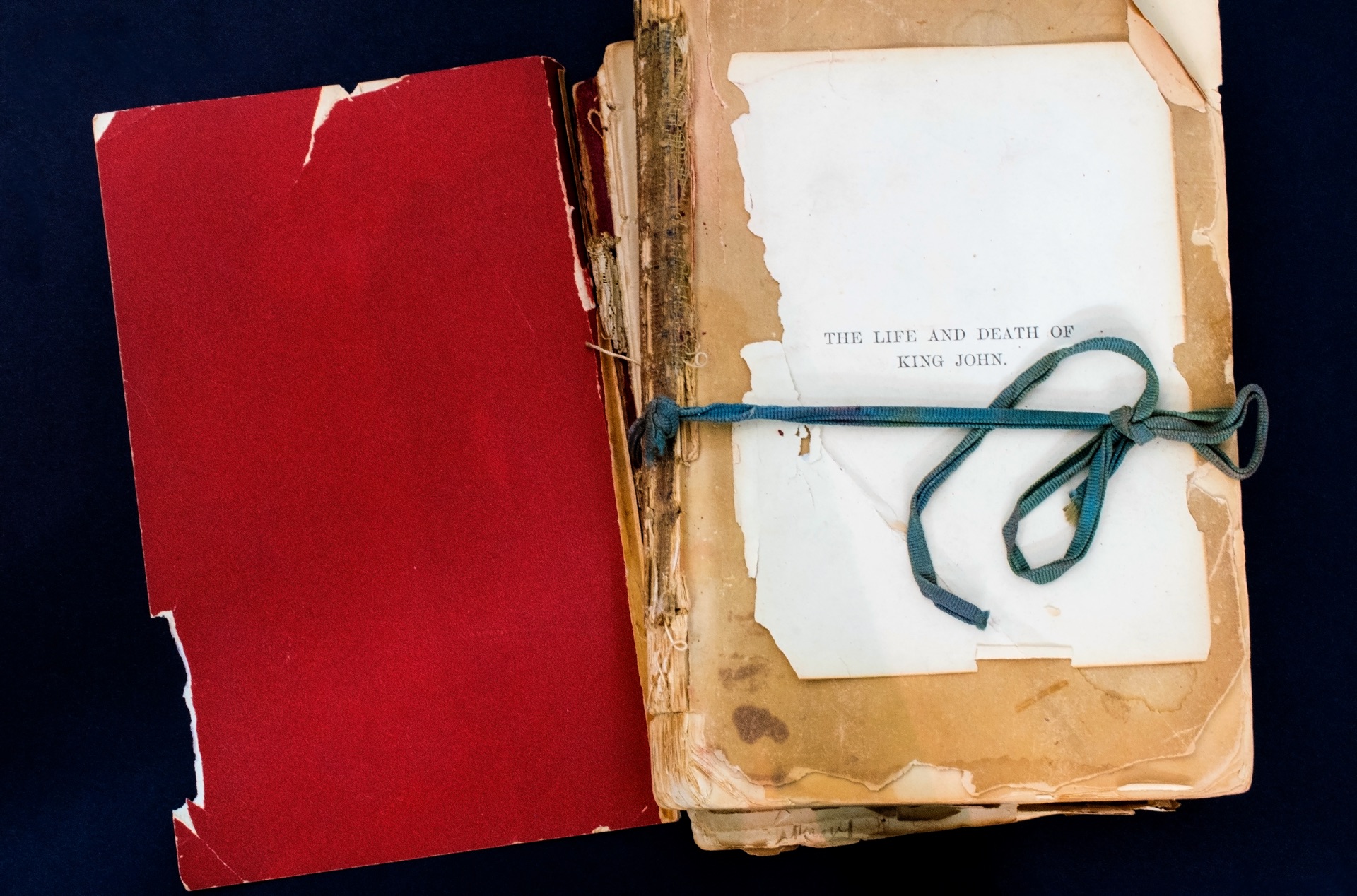

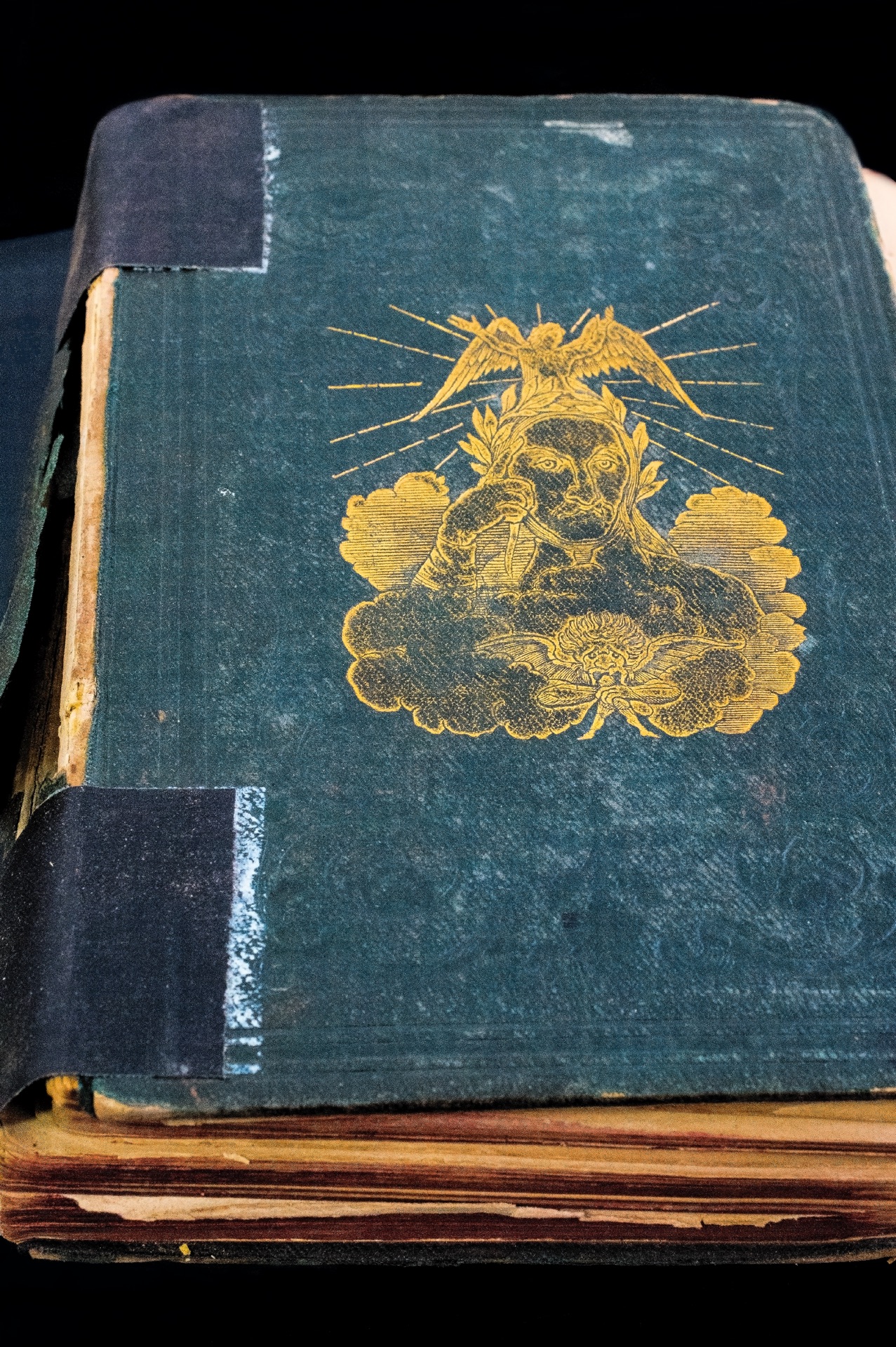

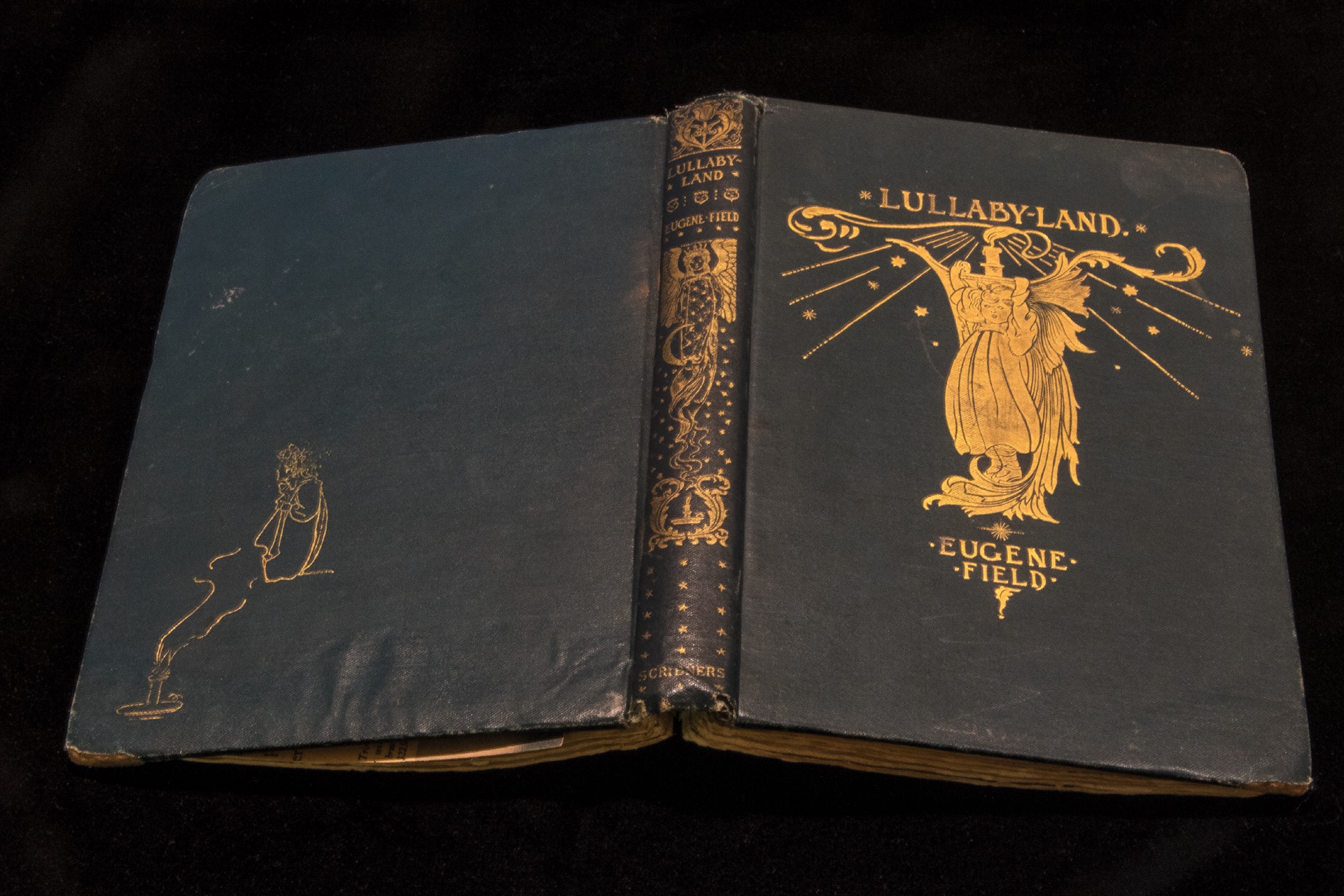

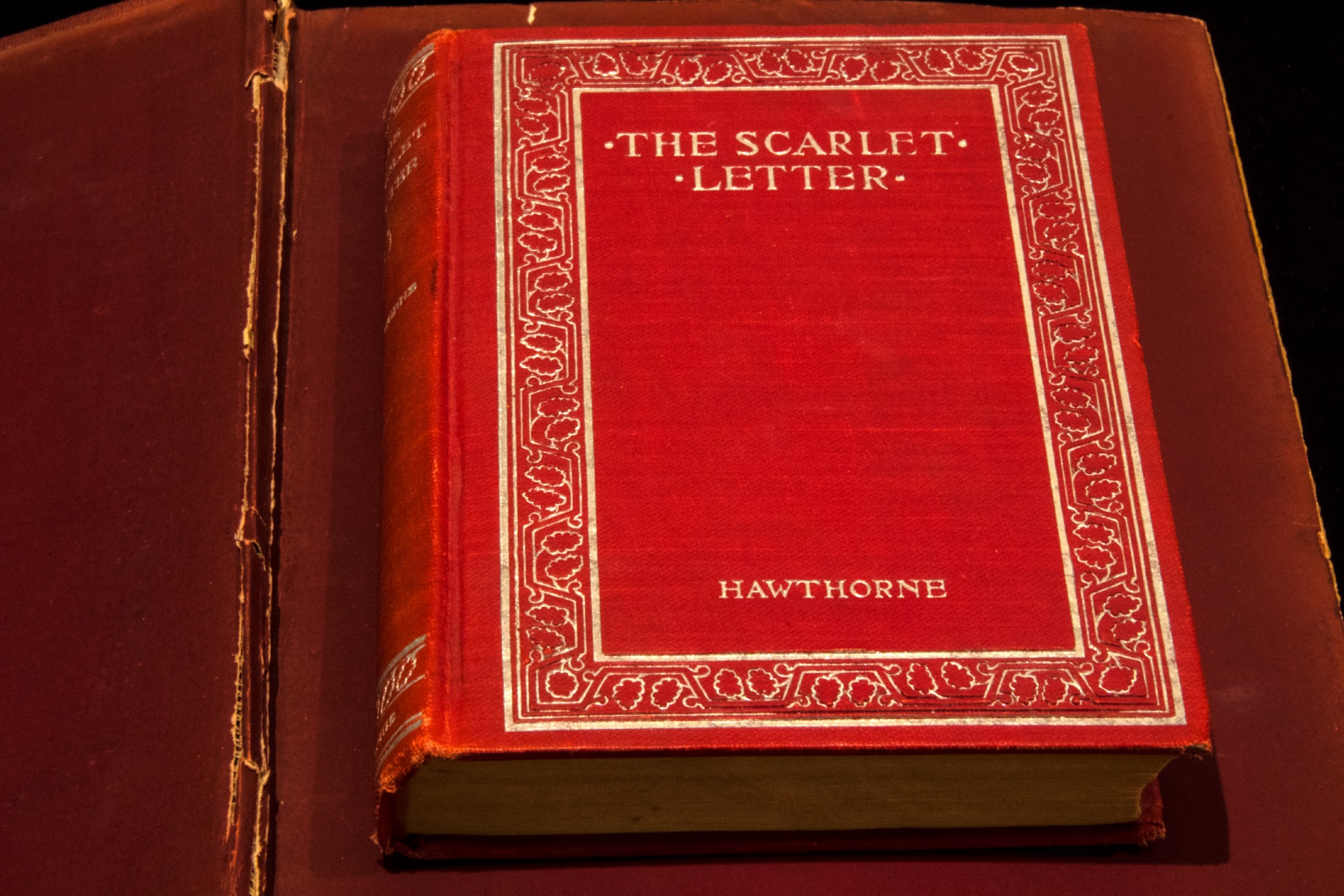

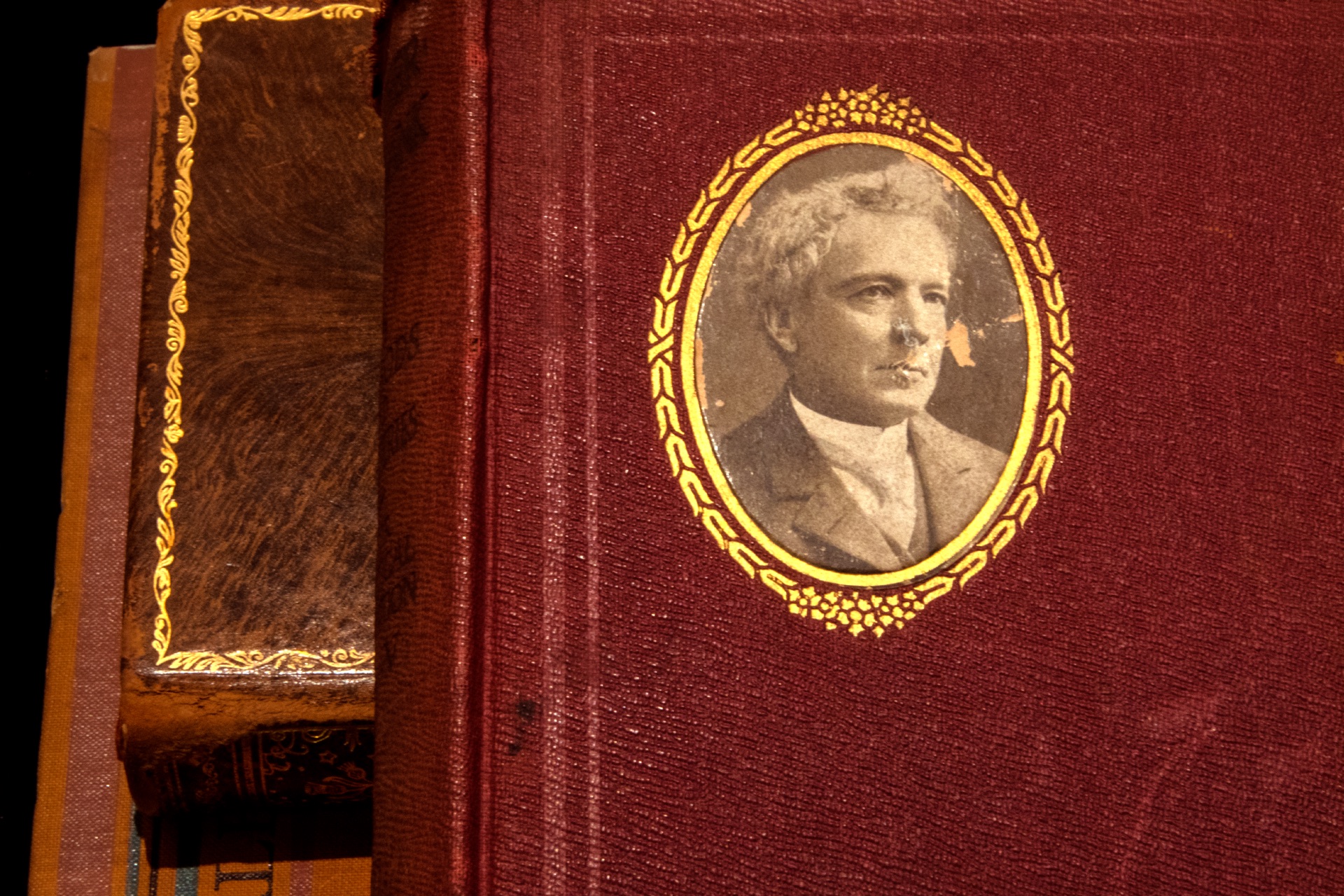

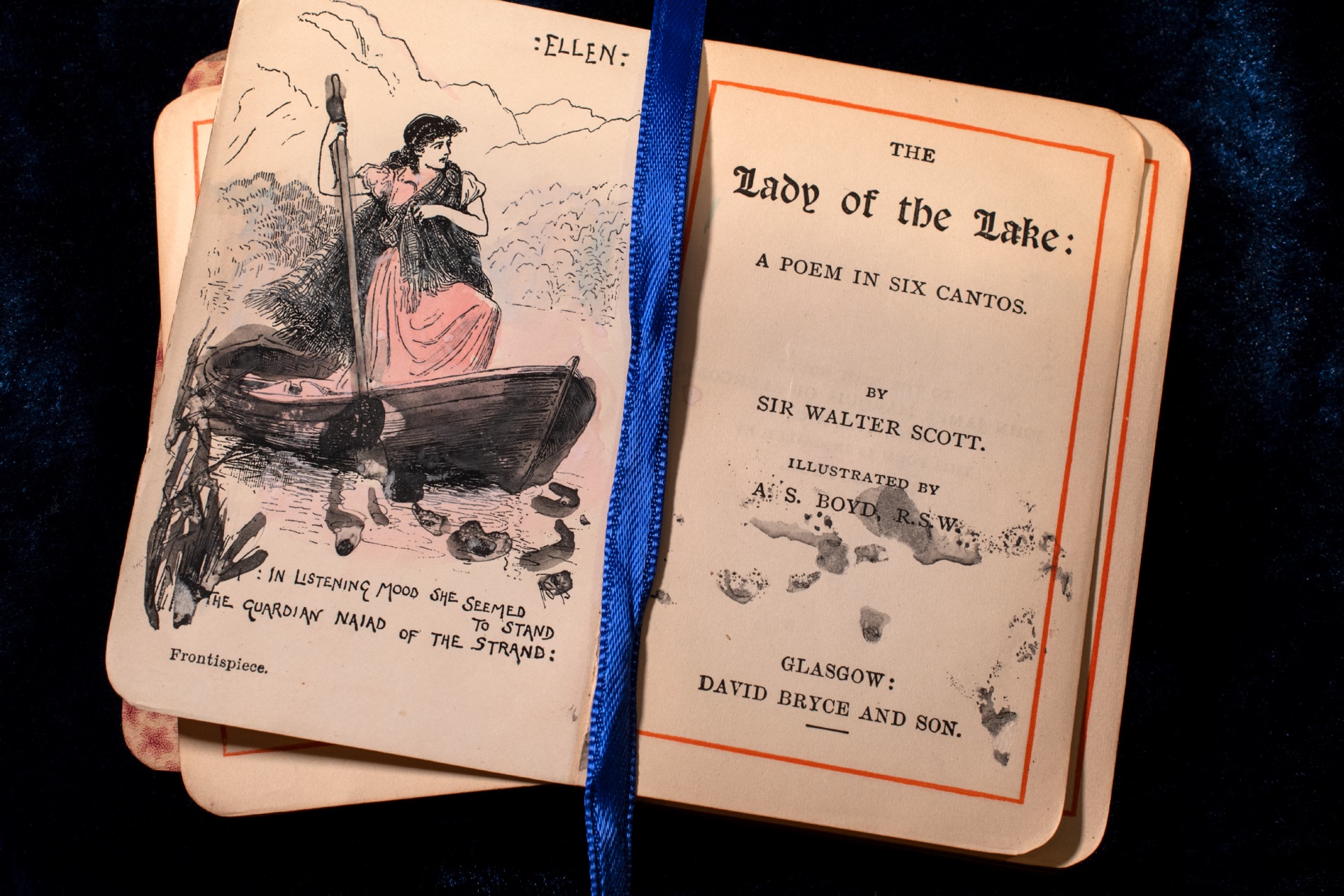

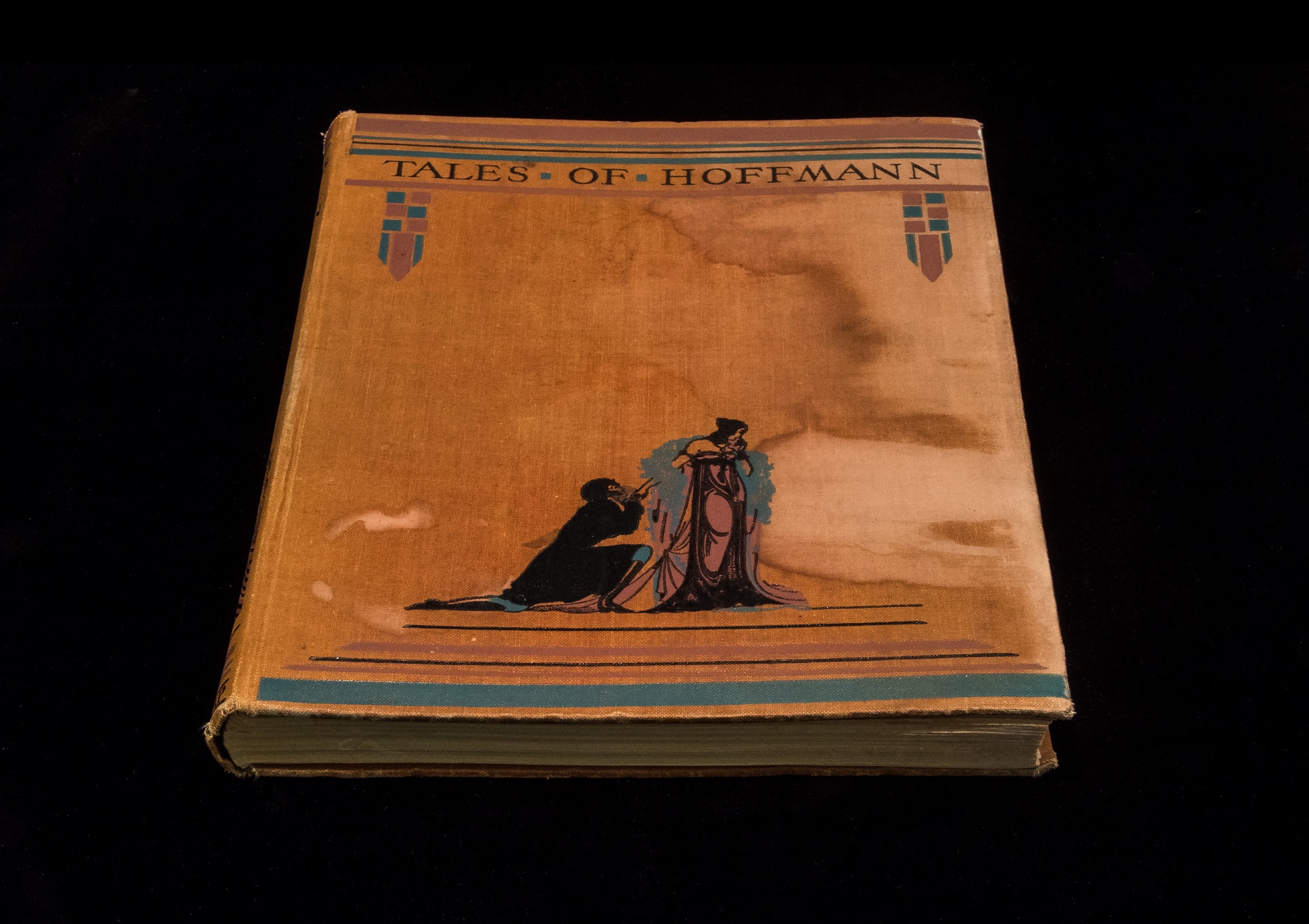

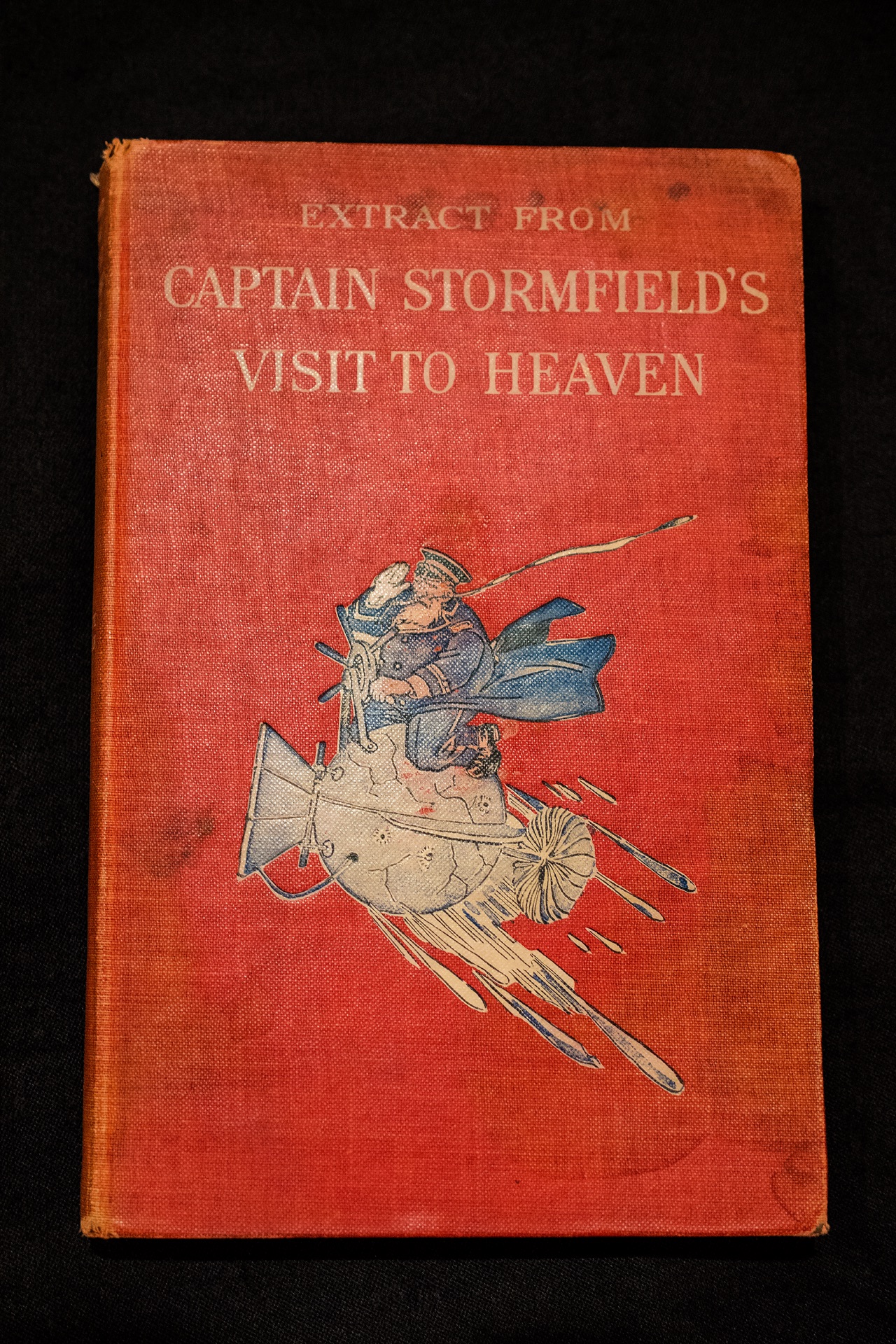

As I first opened boxes, the books began crumbling in my hands; literally turning to dust; the richly colored covers, the bindings, gold embossed titles, pages filled with stories, poems, indexes, chronological tables – the physical beauty of those objects dissolving, disintegrating in front of my eyes. I resolved to photograph them.

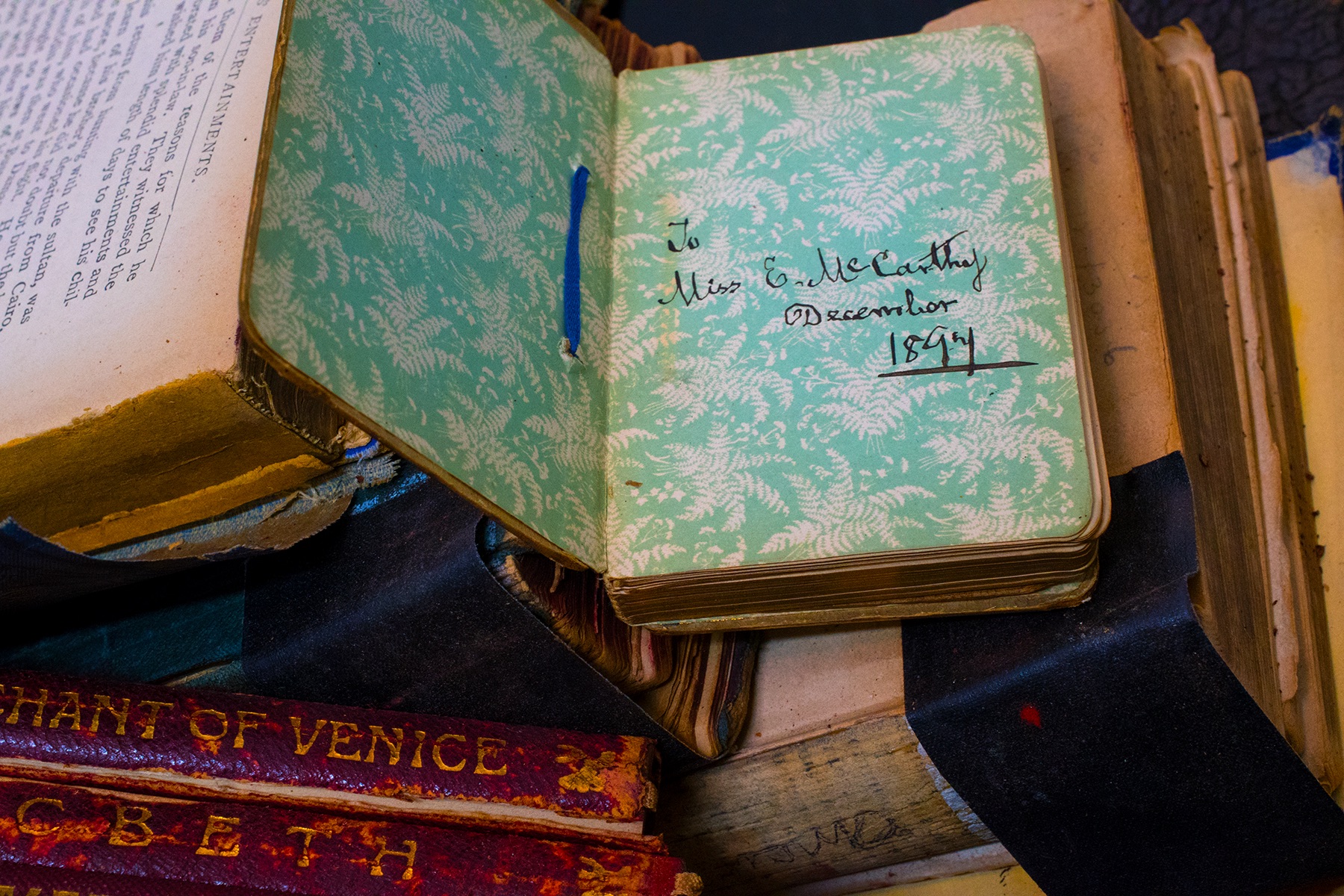

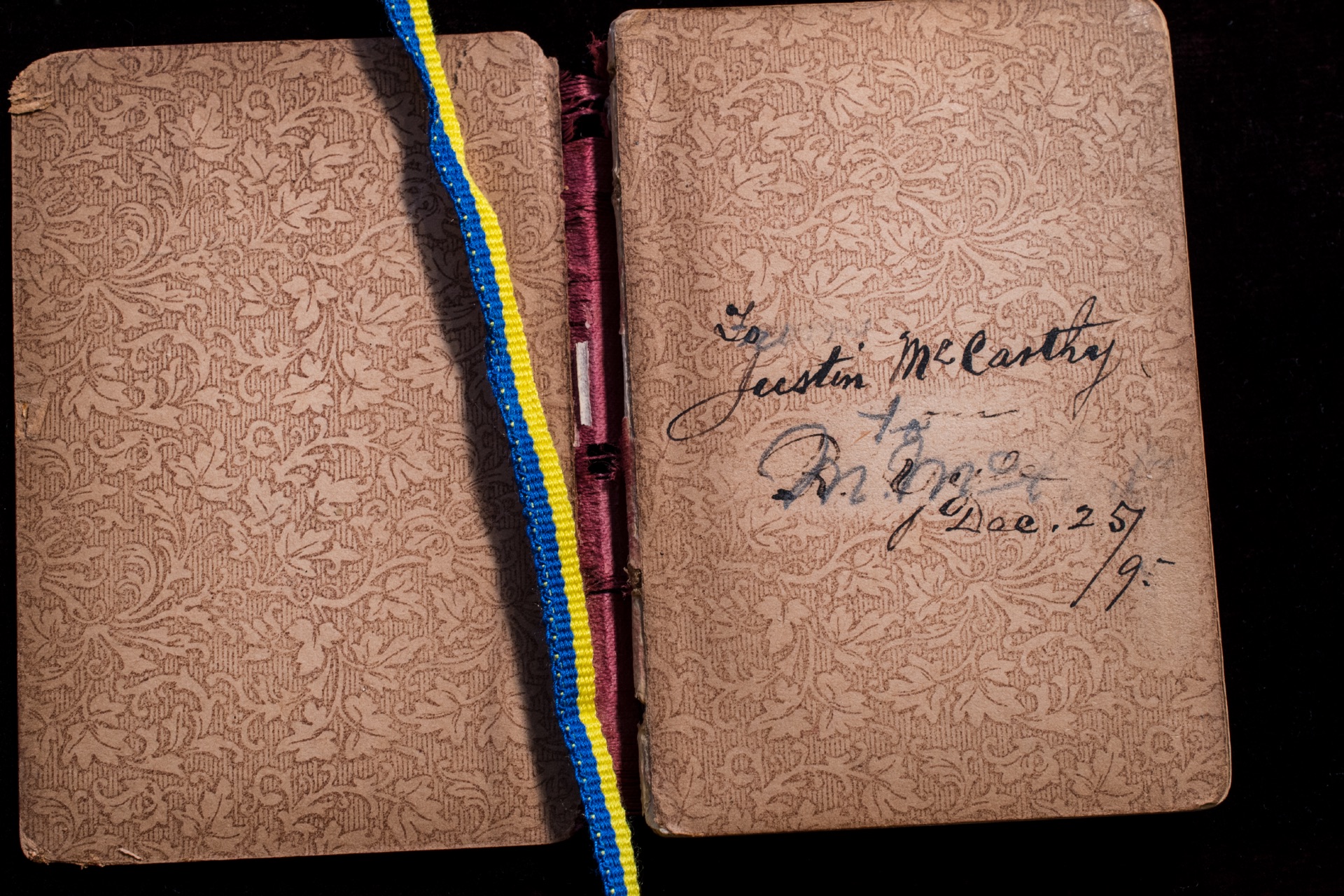

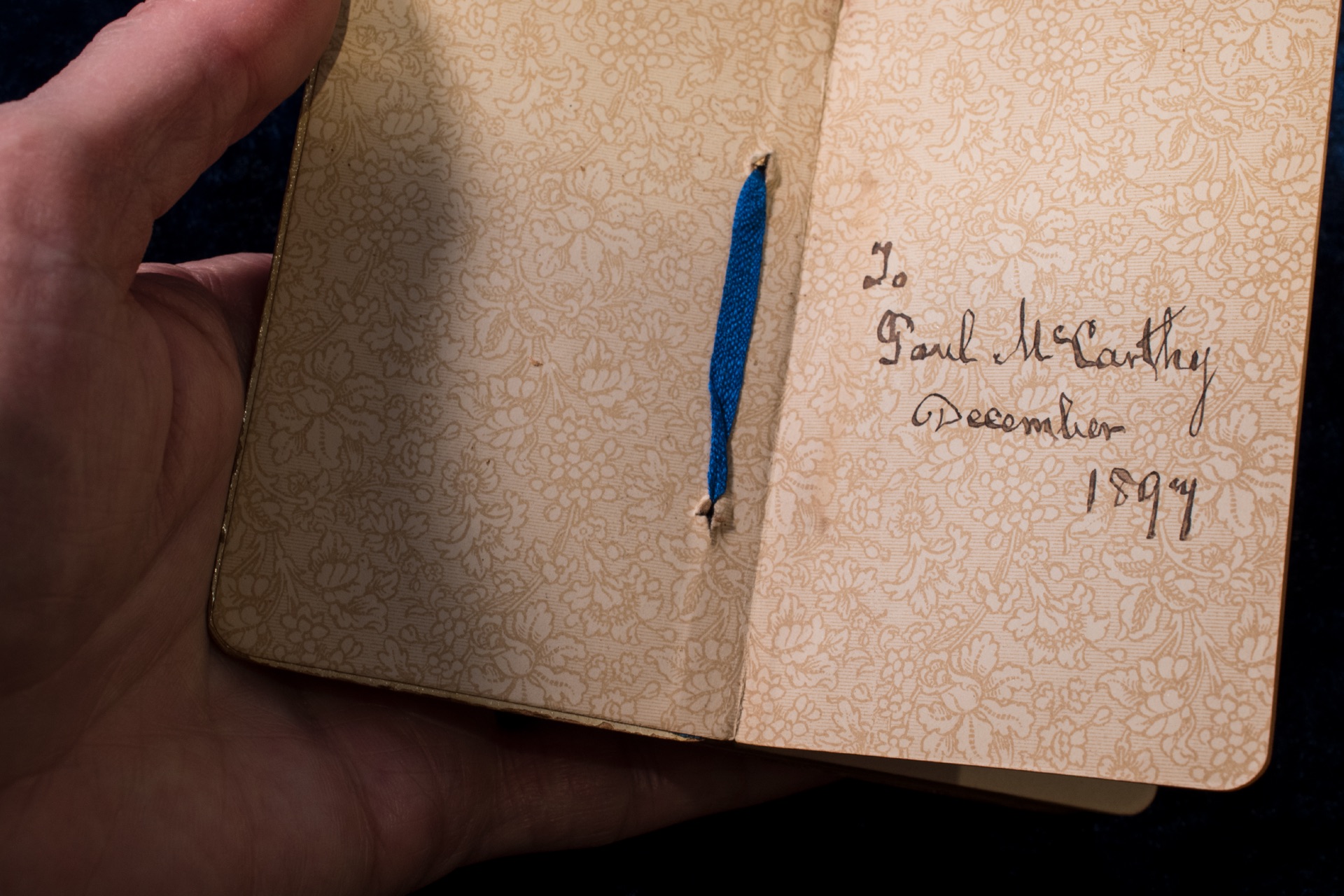

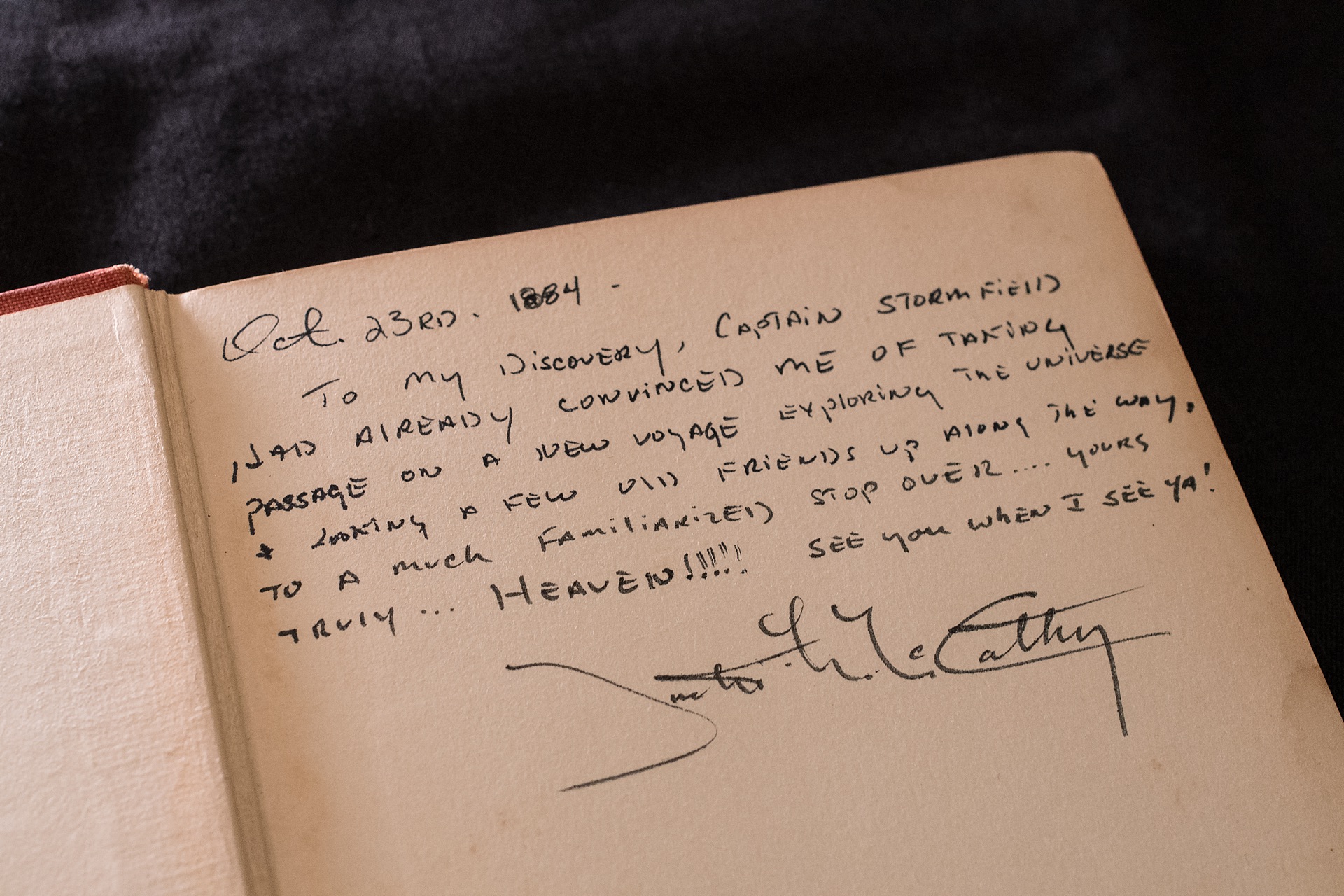

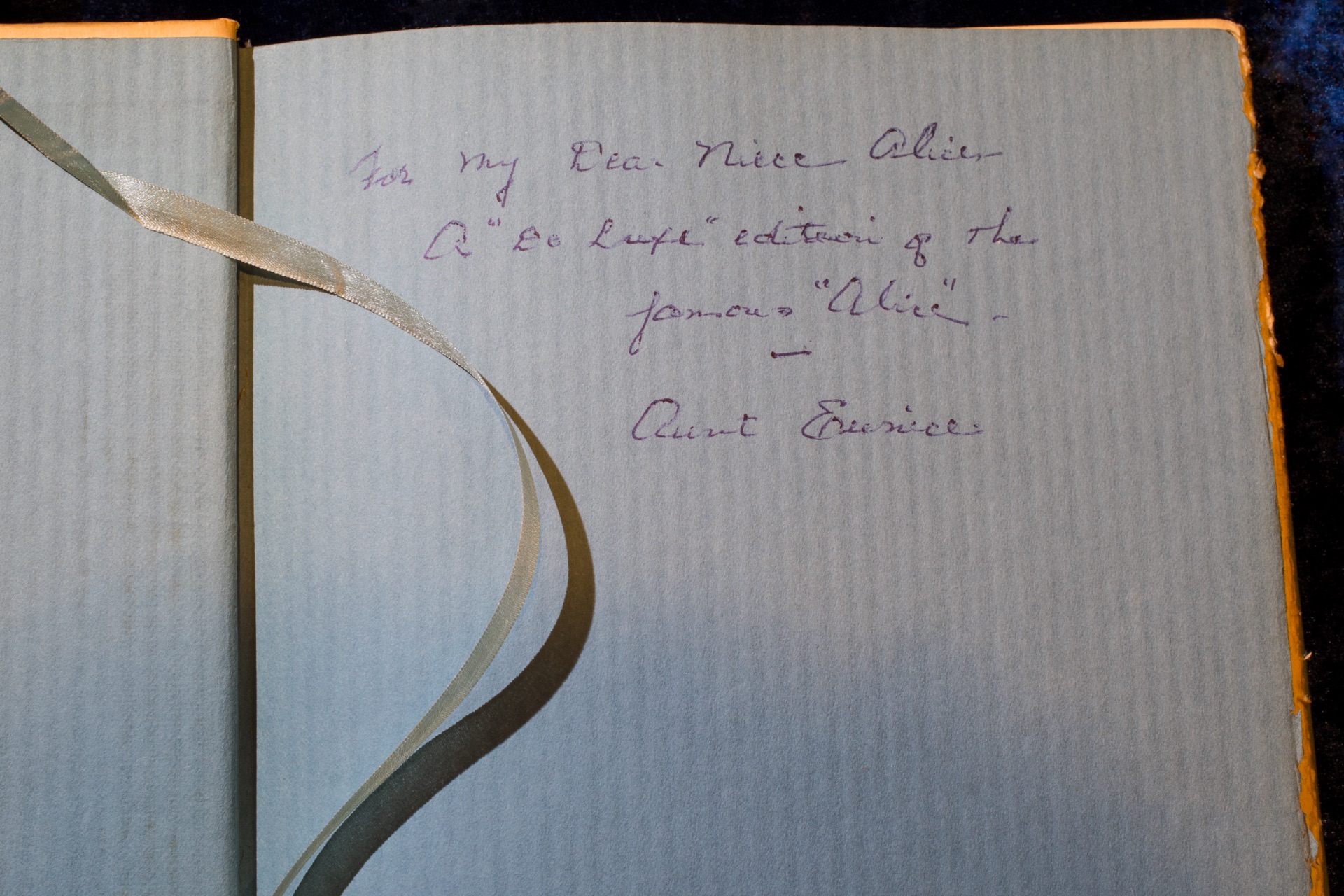

The inscriptions and dedications held a particular fascination; who gifted these books to them?

One inscription was in handwriting I recognized as my own brother Justin’s. No. It was my grandfather Justin’s, signed 1884. How is it their handwriting looked nearly identical across generations?

How do we inherit things? How do we pass them on? In handling their bequeathal, what do we owe our ancestors?

Photographing their books became a meditation on the act of reading, the art of book making, and how we pass our culture from generation to generation. Reading is a mental process that moves us emotionally; but the book is a physical, tactile object. I felt physically connected to my ancestors through the physicality of their books; photographing them, I felt connected to the culture of their time. Reading as joy, book making as art.

In these books, I also see physical proof that storytelling transcends time and culture.